Investigations on This Charming Craft

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

February 3, 2023

As my team, my interns, and I catalog and inventory the Seaport Museum’s collections, we sometimes come across terms like “scrimshaw” and “silkies”—words we wouldn’t have necessarily learned if we didn’t work at the South Street Seaport Museum. All of us had to become familiar with maritime art vocabulary and specific nomenclature to take care, interpret, and share the Museum’s collection with the public.

Sometimes, the name of an artform or craft practice tells you a lot about it. Woolies, for example, are used to describe sailors’ woolworks and sewn pictures, embroidered ships and landscapes produced from around the 1840s until they fell out of fashion around World War I. However, sometimes these common names perpetuate misconceptions.

In the case of Sailors’ Valentines, these two words could evoke so many meanings to any of us. But, as soon as I started to dig a bit more into their origins, I discovered their rich and complicated history. So, let’s briefly talk about the hidden paths of cultural exchange and craft labor that these specific charming works hide.

Revisiting History

Sailors’ Valentines were popular mementos for sailors aboard navy and whaling ships from 1830–1880 and are relatively rare today. Long considered fascinating examples of 19th century maritime craft tradition, these shallow octagonal wooden boxes open to reveal intricate mosaics created from shells of various shapes and colors arranged in complex geometric patterns and motifs, such as hearts, anchors, and flowers. When closed, these boxes could be easily stored, making them ideal for time at sea.

In addition to being a decorative souvenir, these boxes were often given by sailors as tokens of love and friendship to their wives, mothers, sisters, and friends upon a seafarer’s return to North America after months at sea. Personalization such as photographs, names, and initials, as well as sentimental messages were often incorporated into the interior mosaics. Notes often include statements such as: “To a Friend,” “Think of Me When Far Away,” “Remember Me,” “With Love,” “Forget Me Not,” and “Home Again.”

“Sailor’s Valentine” 19th century. Shells, seeds, wood, glass. Gift of the J. Aron Charitable Foundation, South Street Seaport Museum 1988.075.0105

Though these sentimental treasures are referred to as “Sailors’ Valentines” historians have revealed that these works of art had no specific link to February 14th or Valentine’s Day, as well as no specific link to the myth of their creation by lonely sailors.

Originally, these objects were thought to have been made by whalemen who often interacted with crewmen or merchants who would share the latest European art styles—including 19th century ladies’ parlor arts. The Valentines’ popularity was fed by the Victorian collage-making and shell collection craze known as “conchylomania,”[1]From the Latin concha, for cockle or mussel, soon rivaled the Dutch madness for collecting tulip bulbs, and often afflicted the same people; from “Mad About Shells” by Richard Conniff. … Continue reading which filled curiosity cabinets across England, the Netherlands, and the United States.

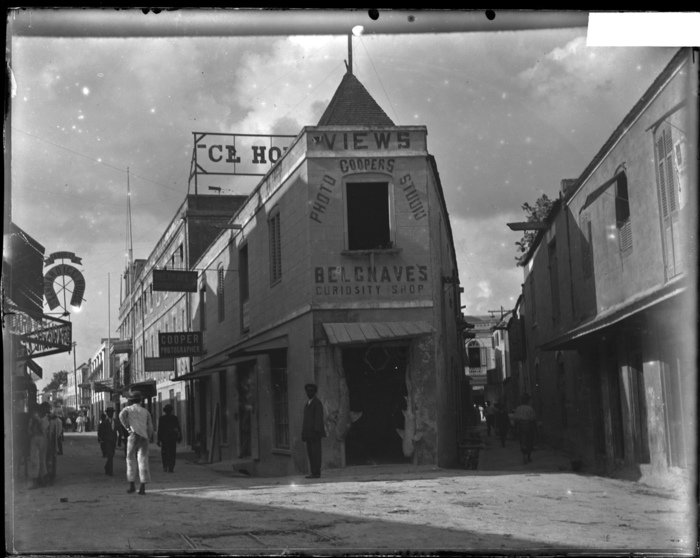

Anna Marlis Burgard’s piece in Atlas Obscura explains, “It wasn’t until the publication of a February 1961 article in the magazine Antiques, by Judith Coolidge Hughes, that the myth of the lonely, artistic sailor began to come undone. Hughes discovered that a woman restoring an antique sailor’s valentine in a Massachusetts collection found an early 1800s clipping from the newspaper The Barbadian in the backing. The clipping mentioned that these “fancy work” items were for sale at Belgrave’s Curiosity Shop in Bridgetown, Barbados.”

Charles W. Blackburne [Cooper’s Photo Studio and Belgrave’s Curiosity Shop, Bridgetown, Barbados] 1897-1912. Gift of John Noll in honor of Richard Waldmann, 2013. Image Courtesy of the International Center of Photography 2013.81.16

Additionally, it is now known that in The Natural History of Barbados, Reverend Griffith Hughes (1707–1758) wrote about women on the island creating beautiful designs from seashells, providing further support for the idea that, instead of solitary sailors, women in Barbados made these precious objects. At the time of its publication in 1750, this compendium was described as lacking accuracy and scholarship, but Hughes had achieved a number of firsts, including the description of a grapefruit, which he called “The Forbidden Fruit,” and the coining of the phrase “yellow fever.” His observations throughout were based upon personal or reliable witness: “This I can with Truth say, that I have not represented one single Fact, which I did not either see myself, or had from Persons of known Veracity.”

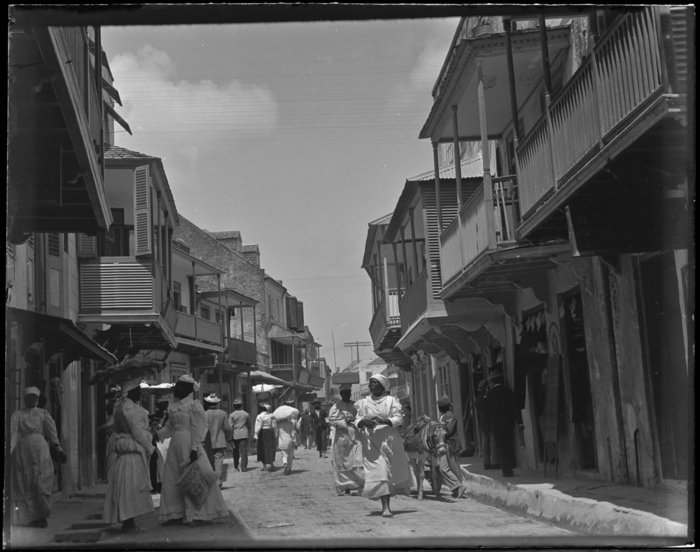

Barbados was a frequent port of call for North Atlantic-based ships, often the very last stop before home. So, similarly to today’s travelers, it’s not too complicated to imagine that sailors would naturally stroll the streets and shops for souvenirs to give to loved ones, while provisions were gathered and vessel repairs were made.

And, as is the case with many works of art, correct attribution and historical understanding of these objects is evolving so that historians and institutions can shine light on historically under-recognized artists, often female, and often of color.

Charles W. Blackburne [Swan Street, Brigdetown, Barbados] 1897-1912. Gift of John Noll in honor of Richard Waldmann, 2013. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography 2013.81.25

Linda Nochlin wrote in her 1971 masterpiece essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” that: “While the recent upsurge of feminist activity in this country has indeed been a liberating one, its force has been chiefly emotional–personal, psychological, and subjective–centered, […] rather than on historical analysis of the basic intellectual issues which the feminist attack on the status quo automatically raises.”

In the field of art history, the white Western male viewpoint has been unconsciously accepted as the viewpoint of the art historian, proving to be inadequate not merely on moral and ethical grounds, or because it is elitist, but on purely intellectual ones. And, in our case here, the historical analysis broads up to the surface this “miracle story.” A miracle given the overwhelming power against women, or people of color, that so many of both have managed to achieve so much excellence, in those areas of white masculine prerogative like science, politics, or the arts.

Contemporary Sailors’ Valentines

This craft is still being practiced today, and little has changed in their making in nearly 200 years. Today’s artists update sizes and rely on more modern materials to make modern Sailors’ Valentines. But, otherwise, the same detailed composition and patterns are at the forefront of the pieces.

Artist and author of “Contemporary Sailors’ Valentines: Romance Revisited,” Pamela Boyton, a resident of Sanibel Island, Florida (home of the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum), uses both shells she collects locally and those she imports for specific colors—primarily from the Philippines—including green and white tusk shells and colorful urchin spines. The first time Boynton saw a Sailors’ Valentine, she couldn’t decide how she felt. “I told my husband, I can’t tell whether it’s really tacky or really beautiful.”[2] “Sailors’ valentine: Love letter to the world” by Stacey Henson. The New-Press. June 18, 2016.

Twenty years later, she’s one of the most well-known artists in the genre.

Portrait of Pamela Boynton. Photo credit Amanda Inscore/The News-Press

Her book’s featured artists hail from Barbados and Japan, as well as the Pacific and Atlantic coasts and even reaching inland to Colorado. United in their craft, their works vary, but often include water themes, such as dolphins, octopi, mermaids, King Neptune, and ships. And, she mentioned how a typical valentine takes hundreds of hours to complete, but as the fitting and gluing process proceeds, the puzzle solving becomes meditative.[3] “Contemporary Sailors’ Valentines: Romance Revisited” by Pamela Boynton. 2016.

Most recently the work of Brooklyn-based artist Duke Riley has been examining and re-interpreting this American folk art craft with modern day references to politics and protest.

Best known for “Fly by Night,” a 2016 performance in which 2,000 trained pigeons outfitted with LEDs lit up the New York sky, and for launching his own homemade Revolutionary War submarine into the path of the Queen Mary 2 cruise ship, Riley is celebrated for sensational public works, as well as a dense, yet meticulously fine-lined, style of drawing he has created since being able to hold a pen.

On view through April 23, 2023 at the Brooklyn Museum, DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash, is the first major exhibition of Riley’s work, showing over 250 pieces made of materials collected from beaches in the northeastern United States to tell a tale of both local pollution and global marine devastation. The exhibition includes large contemporary interpretations of Sailors Valentines’ as well as smaller hand-drawn scrimshaw that Riley has spent three years making, which are made of discarded plastics, instead of whale teeth and walrus tusks that 19th century sailors would have etched: the contemporary analog of marine mammal ivory.

Like his plastic scrimshaw, Riley’s Sailors’ Valentines reference historic maritime traditions, but are made from discarded plastics recovered from New York’s waterways, echoing the 19th century’s geometric patterns, included in octagonal shaped boxes. These large-scale valentines highlight both the volume of plastic waste now found in the world’s oceans as well as the dwindling number of seashells that such objects would have been made from in the past.

Many of us felt these pieces are some of the biggest “wows” of the show. Here, below, I’ve added some detail of one of the three new Sailor Valentine mosaics made from found beach plastics. Do you recognize anything, and if yes, what?

To The New Tork Times Riley said, “As artists, we’re going to have to start thinking differently about the materials that we use.” […] “I knew, when I was a kid, that I either wanted to be a garbage man, an artist, or a thief,” he said. “And I think I became all three.”[4] “Duke Riley: Grand Master Trash” by Melena Ryzik. The New York Times. June 16, 2022.

Sailors’ Valentines remain a beautiful and romantic part of New England and Barbados maritime heritage and cultural exchange. They also clearly remain a site of inspiration for contemporary artists. For myself, I look forward to the next time I come across a new contemporary art piece investigating the relations between maritime social histories, arts and crafts, and the oceans ecosystem.

“Sailor’s Valentine” mid 19th century-mid 20th century. Shells, seeds, wood, glass. Gift of Anna Borrs, South Street Seaport Museum 1988.033

Additional readings and Resources

“In the Ocean, It’s Snowing Microplastics” by Sabrina Imbler. The New York Times. April 3, 2022.

“Ever Thine: A Sailor’s Valentine” by Janie Askew, Research Assistant. Smithsonian Gardens. Published on February 11, 2022.

“Gifts to the Heart, From the Sea” by Jennifer Kohms. The Mariners’ Museum and Park. Published on February 10, 2021.

“Hidden Beneath the Ocean’s Surface, Nearly 16 Million Tons of Microplastic” by Tiffany May. The New York Times. October 7, 2020.

“Mad About Shells” by Richard Conniff. The Smithsonian Magazine. August 2009.

“Sailors’ Valentines” by John Fondas. New York: Rizzoli International Publications Inc., 2002, pp. 7-12.

“Collectibles, The Sailors Valentine: Sea Shells for Sweethearts…” by Tim O’Brien. Victorian Homes, Winter 1984, pp. 18-19, 91.

“Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” by Linda Nochlin, 1971.

“Sailors’ Valentines” by Judith Coolidge Hughes. Antiques, Feb. 1961, pp. 187-189

Explore the Collections

Through the new and improved Collections Online Portal, you can explore highlights from the various collections within the Museum. Whether items are preserved in storage, displayed in Museum galleries, or on loan to fellow institutions, you can digitally discover some of these special objects in digital format.

References

| ↑1 | From the Latin concha, for cockle or mussel, soon rivaled the Dutch madness for collecting tulip bulbs, and often afflicted the same people; from “Mad About Shells” by Richard Conniff. Smithsonian Magazine. August 2009. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Sailors’ valentine: Love letter to the world” by Stacey Henson. The New-Press. June 18, 2016. |

| ↑3 | “Contemporary Sailors’ Valentines: Romance Revisited” by Pamela Boynton. 2016. |

| ↑4 | “Duke Riley: Grand Master Trash” by Melena Ryzik. The New York Times. June 16, 2022. |